Return To The Rifle - A Behind The Core Story

Return To The Rifle - A Behind The Core Story

The Beginning

I bounded down the stairs with the reckless enthusiasm common of a ten-year-old boy on such an occasion. I turned the corner into the living room and was met with the soft glow of twinkling lights and shiny red ornaments. I scanned the base of the tree looking for a long box; my dad had said I was old enough this year. There was no such box. Dejected, I started to walk to the kitchen – and then I saw it. Propped up in the corner, behind Douglas fir branches draped in tinsel, was the rifle that would become my constant companion for the next decade.

That was Christmas morning, 1997.

It was a Ruger M77 chambered in .308 with a Leupold 3-9, the wooden stock and blued barrel showing a life well lived from a previous owner I will never know. I would go on to take my first whitetail with that rifle the following year when I was eleven. I carried it into tree stands around the southeast throughout my teen years and into college; it was a tool of swift dispatch for many a deer during that span, with my last harvest with it coming on the final day of the 2009 South Carolina deer season. In the spring of 2010, I had a buddy talk me into getting a bow – a move that would change the course of my hunting life.

I became obsessed. Bowhunting was a drug that directly attached itself to the synapses in my brain and left me no other hobbies. I completely abandoned rifle hunting without a second thought. I spent the next eight years traveling to any state, outfitter, or friend’s family property that would have me climb trees with a bow in my hand. I had no plans to ever pick up a rifle again. Then, in a flash of events that I remember all too vividly, on a cold commute to work, that all changed.

The Accident

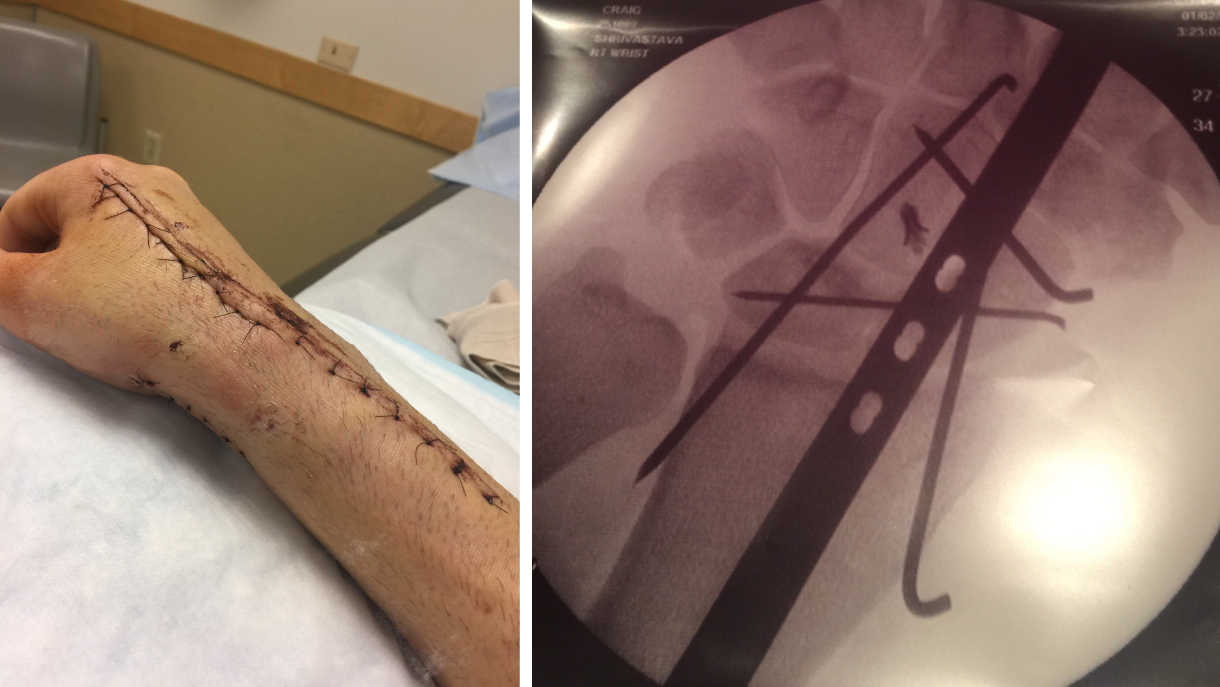

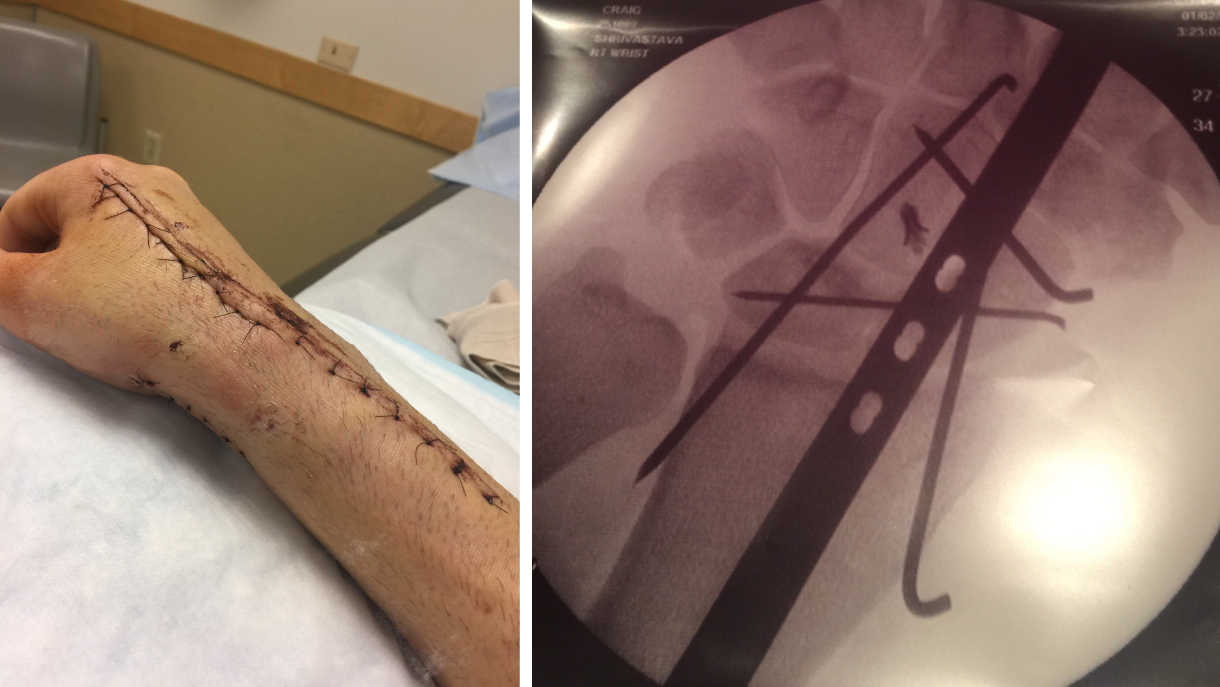

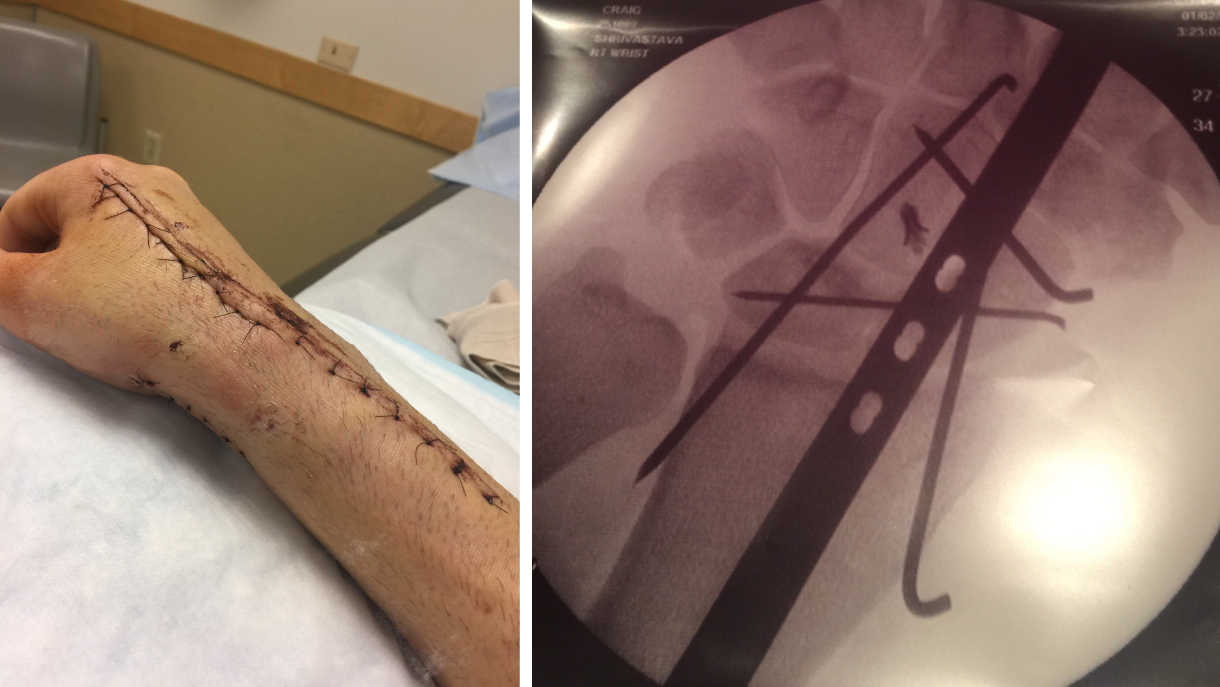

I hit a patch of ice in 5th gear and in an instant, I was sliding on my left hip and shoulder down the road towards the retaining wall, my motorcycle tumbling across the pavement in front of me. I dug the heels of my riding boots into the ground begging for purchase, but there was none to be found. I don’t remember sticking my right arm out to brace for the impact with the wall, I just remember hitting it. A few moments later when I realized that I was very much still alive, I crawled out of the road and began my self-assessment. My legs were not broken. I didn’t have any pain in my back or neck. I reached up to remove my helmet and noticed for the first time that my right hand was folded down and away from my forearm at the wrist. I used my left hand to get my helmet off and complete patting myself down. My right arm was the only injury I could find - I couldn’t believe it. I very easily could have died. Thank God for good riding gear.

I called my wife to come pick me up and drive me to the hospital. As the adrenaline began to wear off and the pain started to pulse through my arm I remember turning to her and saying, “I wonder how long it will take me to be able to draw my bow again?”

The doctor entered the room after sending me for an MRI. “This is the worst wrist injury I have seen in 22 years of practice - we don’t have any good options.” His words stung and didn’t make sense. He went on to tell me that he would need to fuse the wrist solid as that would create the most stable platform for continued use of my hand. I told him about bowhunting and that I needed use of my wrist. He paused and cautiously told me he’d make a few calls.

“Experimental surgery” is an interesting phrase to have come through your ears and into your brain. He told me about one surgeon in Australia that he had contacted that had repaired a similar injury a surfer had sustained on a bad wave after getting worked over in the reef. “I’ve called every wrist surgeon I’ve ever met,” he said. “He is only one that offered any solution other than total wrist fusion.” I asked him about what that surgery would entail and told him not to bullshit me. “I’d say there’s a 50% chance we try it, you do a year of brutal therapy, you can’t deal with the pain, or something tears loose and then we have to fuse it anyway.” I mulled it over for a few moments and then I asked him what he thought about being the first Dr. In the U.S. to be able to publish this surgery in a medical journal. He smiled. “I’ll have my PA get you prepped for surgery tomorrow.”

A few surgeries and many, many hours of PT later, I have a wrist that is about 40% functional. Somewhere along the way it was a real concern of mine that I would never be able to draw a bow again. At that point, I couldn’t hold a coffee cup full of water by the handle without wincing in pain. I started to come to grips with that idea and what it would mean for my life. Hunting had become such a core part of who I was. Spending time outside in the pursuit of animals was my safe place. Hunting was were I did all my best thinking and soul-searching and I had come to take deep satisfaction in being connected to my food in the way that only hunting can provide. I knew I couldn’t give up hunting - so for the first time in a long time, I thought about that old wooden stock and blued metal.

The Return

Due to the loss of flexion in my wrist, I cannot grip a traditional rifle stock. My hand just doesn’t bend that way any more. It seemed that a custom build would be my only option. I had a friend tell me about Jared Walker, owner of Flint Ridge Rifles in Michigan who gives 10% of the sale price of the rifle to the conservation organization of your choosing, which sounded like a damn fine idea. I called Jared and he recommended a stock from Manners that had a vertical grip with a generous palm swell that he thought might work for me. We talked for a while, walked through my wants and needs and he got to work building me a custom 30 Nosler.

I had learned to shoot on an MOA scope from Leupold all those years previous and I wanted to stay with a MOA based system that I knew. More research on my end confirmed that they were still making a great optic, so I called a buddy that works for Leupold and explained the situation. He invited me to come to their HQ for a factory tour, a request I happily obliged. As we walked through the production floor and saw how all of the components come together, I couldn’t help but be impressed at the level of detail and precision that goes into making these tools. I got to talking with one of their engineers on what I wanted out of a scope: lightweight, MOA turrets, and a FFP reticle. After considering these desires we landed on the Mark 5HD for my build, it seemed to be the perfect match. Seeing hard-working Americans build the scope that would rest atop my rifle for years to come was an experience that I won’t soon forget.

I spent the summer getting reacquainted with the mechanics of shooting, searching into the bowels of what I came to call, “sniper school YouTube” and sent a lot of rounds down range. I fell in love with the process of shooting. The controlled breathing and patient application of trigger control all fit into my mind like neatly stacked arrows in the face of a foam target. I had found a new thing to capture my attention and efforts, much like bowhunting had years ago. My confidence with my new rifle grew quickly and I met my self-imposed goal of being dialed out to 400 yards before my elk hunt.

That hunt came and went with no pull of the trigger. I didn’t get to fact-check my months of preparation with crosshairs rested atop meat and bone. And while that is somewhat disappointing, I greatly enjoyed the journey. My return to the rifle has been a lesson for me that there are sometimes alternate routes to the well-worn paths that I have come to know. So much of life is serious. Shooting for me is fun and I intend to keep it that way. As it turns out, I did eventually regain the strength and ability in my wrist to draw a bow. However, I am eager and excited to have added the rifle back into my quiver and I look forward to toting it around the hills next fall in search of meat and good memories.

- Craig Francis (@craigfrancisphoto)

The Redemption

In the Fall of 2020, Craig returned to the wilderness in pursuit of elk. With his rifle by his side, he headed solo into the backcountry and found the success he had been chasing since the accident.